The runner system consists of four components: the sprue, the runner, the gate, and the cold slug well.

The Sprue

The sprue (also referred to as the main runner) is defined as the plastic channel that connects the nozzle of the injection molding machine to the runner. It serves as the first component of the runner system.

Key Terminology Notes (for Clarity in Mold Engineering Context)

Gating System: A critical part of injection molding that controls the flow of molten plastic into the mold cavity, directly affecting product quality (e.g., surface finish, structural integrity).

Cold Slug Well: A recess in the runner system designed to trap the first, cooler (and often less uniform) portion of molten plastic (called "cold slug") to prevent it from entering the mold cavity—this detail is pre-emptively clarified as it’s a core function tied to the system’s overall purpose.

Sprue vs. Runner: The sprue is the primary, direct channel from the machine nozzle, while the runner (or "sub-runner") distributes plastic from the sprue to multiple gates (if the mold has multiple cavities), hence the hierarchical relationship described in the text.

Runner

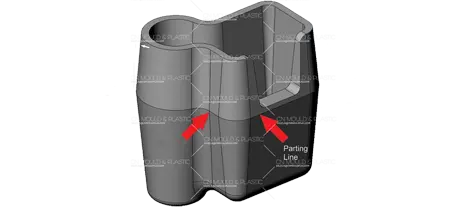

The runner (also called the "distribution channel") links the main sprue to the gate of the inner mold, letting molten plastic flow into the inner mold. For two-plate molds, the runner is set right on the parting line. When designing a runner, you need to pay attention to its cross-sectional shape and size.

There are usually four types of runner cross-sections: circular, trapezoidal, modified trapezoidal, and hexagonal.

• From the perspective of injection pressure transfer: the larger the cross-sectional area, the better.

• From heat transfer efficiency: the smaller the cross-sectional surface area, the better.

So the higher the ratio of cross-sectional area to surface area, the more effective the runner is. Circular cross-sections cool faster than square ones, so they’re the best design choice.

The runner’s diameter is related to its length—longer flow paths need a larger diameter. At the same time, you want the runner to be as thin and short as possible. Every type of plastic has a minimum diameter requirement: if it’s smaller than that, the plastic can’t reach the mold cavity. Usually, the runner diameter is 1mm thicker than the plastic part’s wall thickness. This prevents the plastic in the runner from solidifying before the part does, which would stop proper pressure holding.

Gate Design Requirements

(1) A gate is a short, narrow channel with a small cross-sectional area that connects the runner to the mold cavity. The small cross-section is designed to achieve these effects:

a. The gate solidifies quickly right after the cavity is filled;

b. Trimming the gate (removing the leftover plastic) is easy;

c. After trimming, only a tiny mark is left on the part;

d. It’s easier to control plastic filling for multi-cavity molds;

e. It reduces over-filling.

(2) There’s no strict rule for gate design—most of it is based on experience. But you need to balance two key factors:

a. The larger the gate’s cross-sectional area and the shorter its length, the better (this cuts down on pressure loss when plastic flows through);

b. The gate needs to be narrow enough to cool quickly and stop excess plastic from flowing back. It should be in the center of the runner, and its cross-section should be as circular as possible.

(3) A gate’s size is determined by its cross-sectional area and length, but these factors also affect its optimal size:

a. The plastic’s flow properties;

b. The part’s thickness;

c. The amount of plastic injected into the cavity;

d. The plastic’s melting temperature;

e. The mold temperature.

(4) When choosing the gate location, follow these principles:

a. Put the gate on the thickest part of the part. This keeps the gate cool slower, helping molten plastic fill the cavity fully (no dents or defects).

b. The gate should let plastic take the shortest path with the least direction changes—this minimizes energy loss. Usually, putting it at the part’s center works best.

c. The gate location should help release air from the cavity. If molten plastic seals the vent too early, air gets trapped (ruining the part). So if needed, add a vent where the plastic reaches last.

d. Place the gate directly facing the cavity wall or a large core. This makes the high-speed plastic hit the wall/core first—slowing it down, changing its direction, and filling the cavity smoothly. It eliminates obvious weld lines and prevents plastic from breaking.

e. Don’t use too many gates. More gates mean more weld lines. Unless necessary, stick to 2 or fewer.

f. The gate should make the plastic flow distance from the main sprue to all parts of the cavity equal (or nearly equal)—this reduces weld lines.

g. For parts with cores or inserts (especially long, thin cylindrical parts like connector injection molding components), avoid off-center gating. This prevents cores from bending or inserts from shifting.

h. Don’t place the gate where it causes plastic to "break." If a small gate faces a wide, thick cavity, high-speed plastic will face strong shear stress—causing issues like spraying or creeping. Sprayed plastic can fold, leaving wave marks on the part.

i. When plastic shoots through the gate into the cavity at high speed, it creates "molecular orientation." The gate location should avoid the bad effects of this and use it to benefit the part instead.

j. When deciding the gate location and number for a mold, check the "flow ratio" (total flow path length ÷ total flow path thickness) to make sure plastic can fill the cavity. The allowed flow ratio changes based on the plastic’s properties, temperature, and injection pressure.

k. For flat parts (which easily warp because of uneven shrinkage in different directions), using multiple gates works much better.

l. For frame-shaped parts, place gates diagonally—this reduces warping from shrinkage.

m. For circular/ring-shaped parts, use a tangential gate. This cuts down on weld lines, strengthens the welded area, and helps release air.

n. For parts with uneven wall thickness, keep the flow distance consistent from the gate—this avoids swirling plastic.

o. For shell-shaped parts, use a center gate that fills the cavity evenly—fewer weld lines.

p. For cover-shaped, long thin cylindrical, or thin-walled parts (to prevent under-filling), use multiple gates and add "process ribs" (extra thin plastic ribs to help flow).

These gate location rules might conflict sometimes—you need to adjust based on real-world situations.

(5) Gate Balancing

If you can’t get a balanced runner system, use gate balancing to make sure all cavities fill evenly. This works well for multi-cavity molds. There are two ways to balance gates:

• Change the length of the gate channel;

• Change the gate’s cross-sectional area.

If the mold cavities have different projected areas, the gates need balancing too. To set the gate sizes:

1. First decide the size of one gate, then calculate the ratio of that gate size to its corresponding cavity volume.

2. Use that ratio to figure out the size of every other gate (matching each to its cavity).

3. Test the mold with actual plastic—then adjust until the gates are balanced.

If one mold makes two or more parts (and some parts have thinner walls):

• The runner for the thinner parts needs to be thicker (how much depends on the part size).

• Thicker parts let plastic flow better, so they need normal pressure. Thinner parts have worse flow, so they need more pressure.

• If you don’t adjust, the thicker parts might get flash (extra plastic seeping out) while the thinner ones under-fill. Making the runner for thinner parts thicker fixes the pressure loss.

Cold Slug Well

It’s also called a "cold slug trap." Its job is to collect the cold plastic that forms at the start of the injection (the "cold slug"). This stops the cold plastic from getting into the cavity (which would ruin the part) or blocking the gate.

• A cold slug well is usually placed at the end of the main sprue.

• If the runner is long, add a cold slug well at its end too.

English

English  français

français  Deutsch

Deutsch  Español

Español  italiano

italiano  русский

русский  português

português  العربية

العربية  dansk

dansk  Suomi

Suomi  Svenska

Svenska  norsk

norsk