Capability

- Injection Mold for Export

- LSR Mold for Export

- BMC Mold For Export

- Die Cutting

- Foam Slitting & Converting

- Thin Sheet Extrusion

- Post Injection Process

- Assembly Automation

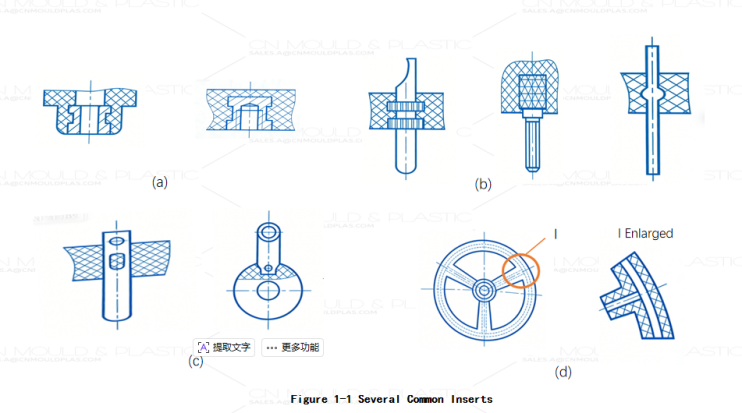

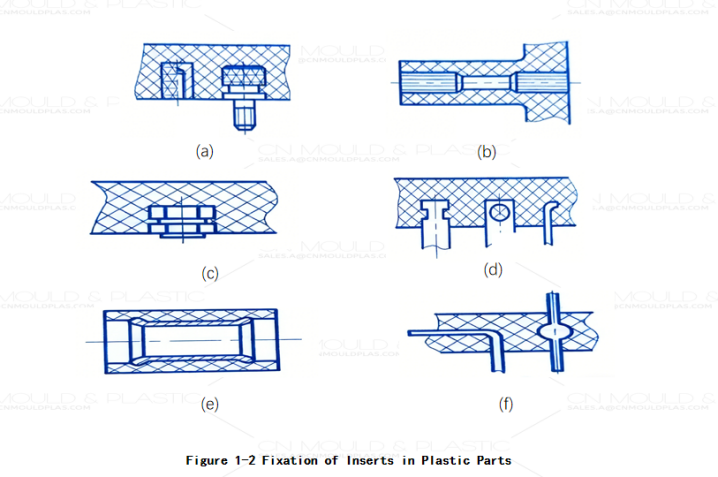

- Turnkey Insert Molding System

- Design for Manufacturing

- Design of Fixture (Jig)

- Rapid Prototyping

- Metal 3D Printing

- Metal 3D Printing_copy20260212102551

Get Instant Quote

What are you looking for?

English

English  français

français  Deutsch

Deutsch  Español

Español  italiano

italiano  русский

русский  português

português  العربية

العربية  dansk

dansk  Suomi

Suomi  Svenska

Svenska  norsk

norsk